How to Photograph a Train, with Emma Nettleton

A remarkable set of photos from 1885, and a reflection on the railway enthusiast space

It’s the spring of 1885, and Wodonga railway station is bustling in the wake of Victoria’s new golden age. A shiny steam locomotive from Beyer, Peacock of Manchester waits to shunt its goods consist into a siding before becoming the next train to Melbourne. There are already passengers on the platform, watching these goings-on with a humdrum air, when a disturbance on the tracks sparks their attention. Goodness, not an accident? No – it’s something even more extraordinary: someone has brought a horse and wagon laden with photographic equipment onto the tracks!

Immediately, everyone is drawn towards this exciting new technology, watching the bubbling brew of collodion and coating of a fresh glass plate. While their companion whisks the plate under an orange tarp, the photographer meticulously sets up their camera into position, their captive audience quite unsure how to proceed. The little girls on the platform shuffle about, blissfully unaware the long exposure time would conveniently censor their faces. The women beside them are aghast; wasn’t there a tale that these devices could capture your souls? The male passengers echo their sentiments, jaws dropped under their impressive moustaches. The railwaymen seem incredulous, but strike a pose against their beloved locomotive; perhaps being in this frame will make good with the Commissioner, as uneasy as this exercise feels.

And as the plate is clicked back into place, the moment is captured for eternity, left to our interpretation. Were the bystanders at Wodonga gobsmacked by what this paraphernalia could do… or that a woman was wielding it?

Fast forward nearly 140 years later. Steamrail Victoria is holding their biannual Open Days at the Newport Workshops. Once the mammoth industrial cauldron and employment hub of the former Victorian Railways (VR), it is now the home of Steamrail’s proudly restored heritage locomotives and carriages. They are glorious machines that have seen many miles of stories, but my railway enthusiasm extends to the buildings themselves; so after I have my picture-perfect frame of the Tait suburban set stood at the Garden Platform, I head over to the clocktower and former VR admin office. As I point my Android phone camera around the beautifully restored rooms, taking in as much detail as I can, the volunteer I’d been having a lovely chat with throws me off guard.

“Isn’t it a bit… unusual, you know, to come down here and do what you’re doing in such a… male-dominated space?”

Now, full disclosure: my relationship with the ideals of femininity and womanhood, and gender therein, is fraught and tenuous. But I have made peace with historical spaces taking my assigned-female-at-birth status very literally. Especially because there are often instances like these where I can use it to make a point.

“Well, it does stick out a bit. But that’s also why you keep at it, y’know?”

I wondered then what was more unusual: my presence amidst coal fumes and testosterone with a cheap, now-ubiquitous photographic device – or a woman doing the very same thing back when a camera took up the space of a shed and also cost you one?

Meet Emma Nettleton

If you’ve spent enough time scouring through Victorian photo archives, you might be familiar with the name Charles Nettleton. He mastered the art of the long-exposure landscape, leaving us stunning panoramic views of fledgling Melbourne’s streets, ports, reservoirs, and wetlands. He is also responsible for the only surviving photos of famed bushrangers Harry Power, Captain Moonlite, and our good friend Ned Kelly; he even has a Coburg connection, a cell reserved in Pentridge Prison that he used as a makeshift dark-room for prisoner mugshots.

But this ain’t about him.

Emma Margaret Miles was only 19 when she met and married Charles in 1851, a doughty Northern Englishman dabbling in the new wet-plate collodion technique. No doubt London was a very saturated market for a photographer, so with her young daughter (also called Emma) in tow, she joined her husband’s quest for photographic gold to the shores of Victoria. She couldn’t have predicted how it would all go!

The clipper that carried Emma and 429 other optimistic souls was the ill-fated SS Schomberg, whose captain James ‘Bully’ Forbes was more concerned about breaking marine speed records than the welfare of his precious cargo, humans included. With a battle cry of ‘Hell or Melbourne’, he ended up choosing hell – the Shipwreck Coast that claimed many a vessel who failed to thread the eye of the needle around Cape Otway. The spot where she succumbed to the rocks near Peterborough in December 1855 is now a scenic V/Line coach stop on the Great Ocean Road.

Luckily there was no loss of life reported; the same could not be said of the cargo, which included several rails and carriages intended for the Geelong and Melbourne Railway Company. That wouldn’t be the first time the railways would dog Emma around…

The survivors from the Schomberg wreck were taken to Port Fairy where they would go their respective ways. Shipping lists tell us Emma and her family finally arrived in Melbourne from Launceston in 1856, now with another daughter, nine-month-old Elizabeth. This contradicts older biographies of Charles that quote him as having started his Victorian practice just in time to photograph Australia’s first ever railway run, in 1854 from Flinders Street to Port Melbourne.

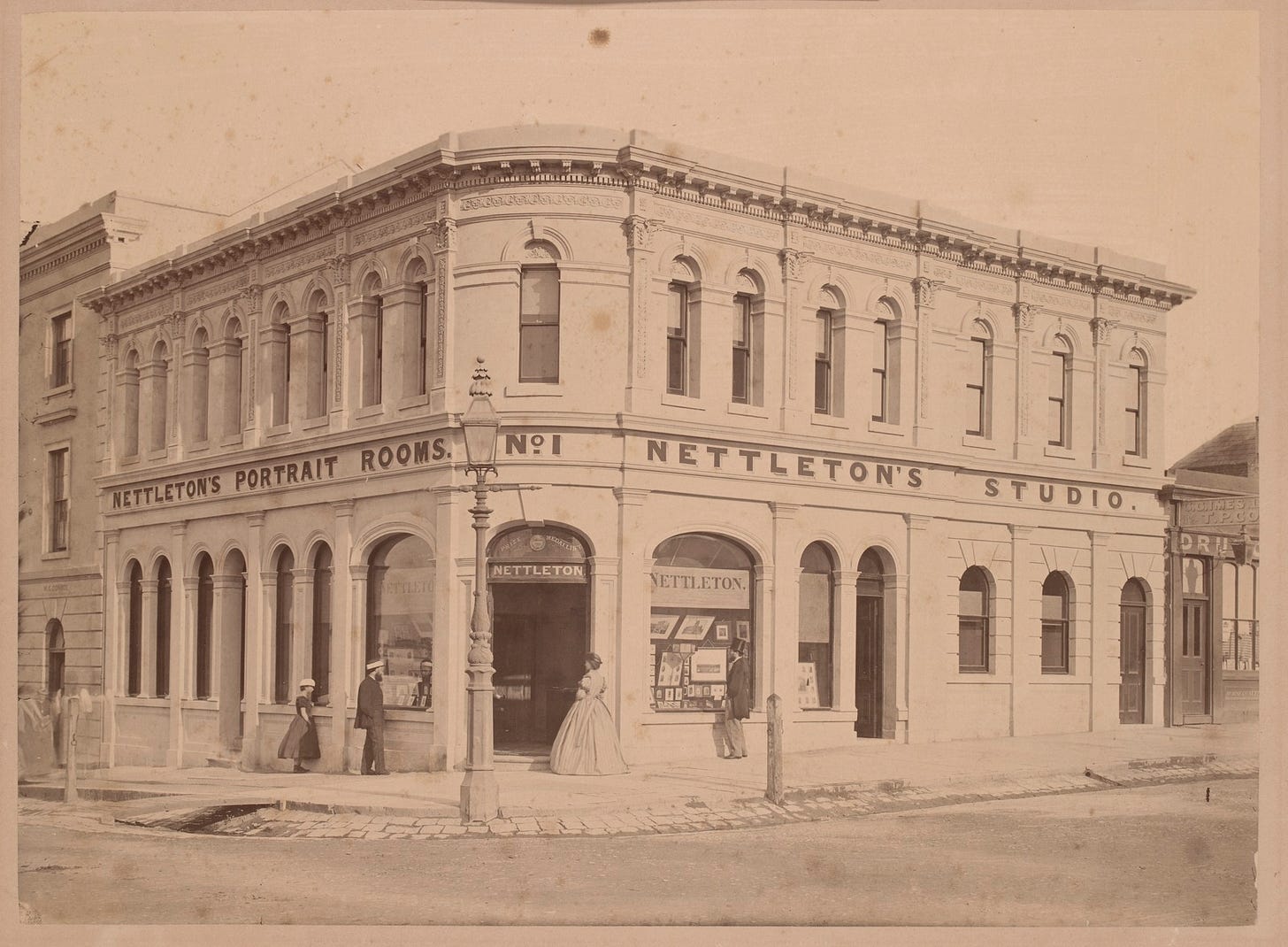

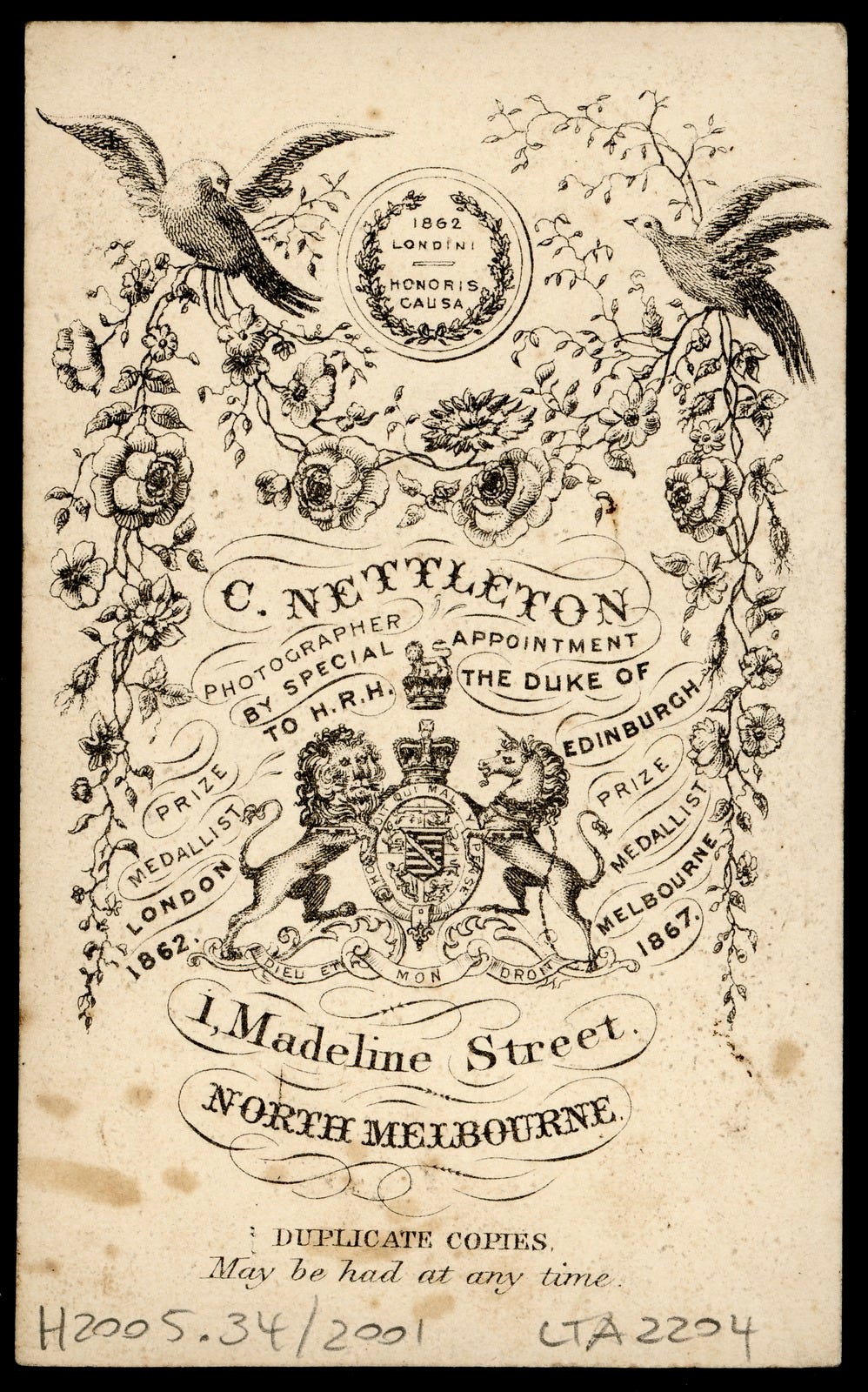

Whether or not he took that photo, by 1858 Charles was settled enough to open his own portraiture studio. However, it was in landscapes where his talents truly lay, and the city council caught onto them soon enough. They had him climbing every tower, hill, and generally tall structure to get the best views of Marvellous Melbourne possible; and after his panoramas from the GPO clock tower won him accolades, he became the official photographer for the Duke of Edinburgh’s visit in 1867. With fame came money, and with money came a swanky new purpose-built studio at 1 Madeline Street, (then) North Melbourne. Today, this spot is occupied by RMIT Building 100 on Swanston Street.

So what was Emma doing while her husband was cavorting with royalty? Like most middle-class women of the time, caring for her rapidly growing family at their residence close by at 19 Madeline Street. But this prosperity comes tinged with tragedy. In 1870, Emma gave birth to a stillborn son; four years later her beloved second-oldest daughter Elizabeth, born shortly after the shake-up from the Schomberg, died of a sudden illness aged only 18. She bore her husband through the weight of their loss as he grappled with competitors aiming to profit off his work; he successfully sued one of them, a J. Pyrke of Collins Street, for damages in 1872. Emma would later find herself defending her own honour at the Carlton courts when a neighbour sued the couple over her allegedly aggressive, bitey dog!

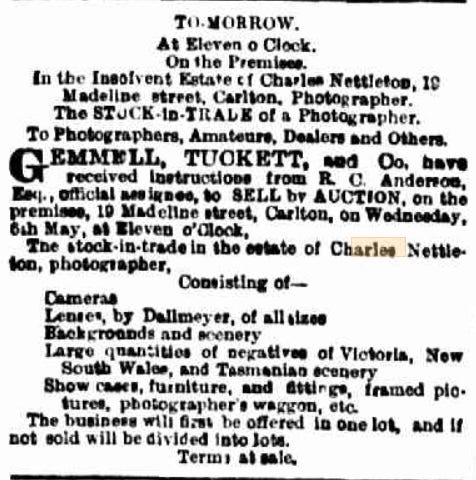

All exciting new technology has its time in the sun, and Charles could see it setting through his wide lens. In 1879 he applied for a patent for a variation on the collodion process he called ‘zincography’, but it found no takers. By the 1880s the new, faster, simpler dry-plate process was swiftly putting Charles out of business; to supplement the family income, Emma ran her own ‘fancy repository’ in the Victoria Arcade on Bourke Street selling ball masks, haberdashery, and fashionable gifts for the ladies doing The Block. It’s not enough, and in April 1885 Charles was officially declared insolvent after failing to pay the rent on his studio, forced to sell all his assets – cameras included.

Just as their hopes were sinking with the Schomberg, the Victorian Railways threw the Nettletons a life raft…

Who really photographed those trains?

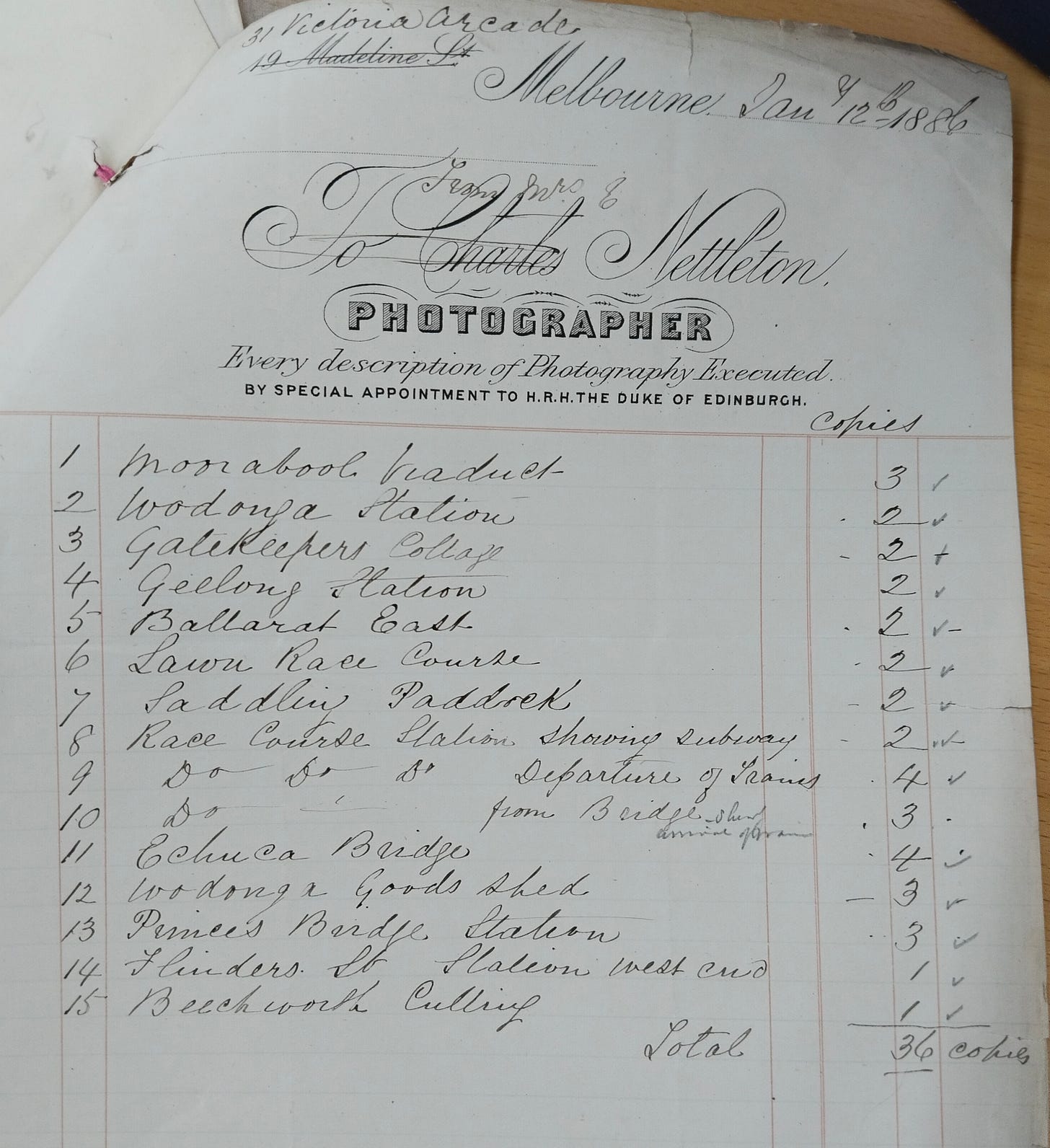

In March 1885 the VR put out a tender for photographers who could document their finest infrastructure and rolling stock in time to present at the following year’s Colonial and Indian Exhibition in South Kensington, London. Charles ended up winning the tender, beating several prestigious Collins Street names; whether VR picked him on past glory or because his happened to be the lowest quote, we will never know. A list of locations and landmarks was handpicked and sent to him, with the photos to be developed, mounted, and shipped all by early December.

However, Charles’ insolvency throws a spanner into the works, and there is a twist in the VR paper trail. The list of photos required by October 1885 is much shorter than before, and later updated to be credited to Emma, not Charles. Initially it is requested that Emma supply the images on behalf of Charles who would execute the order and receive the money, and her letter to the Railway Department in December 1885 states that she has done as much. Then by January 1886, with the photos now in safe storage over the ocean, the VR commissioners credit Emma with the complete list of photos and the money to her Victoria Arcade shop – and with the sign-off in February, they even name her as the photographer!

So what really transpired? It’s not unlikely for Emma to have picked up the art of collodion photography from observing and assisting her husband. Perhaps not all of Charles’ equipment was lost in the estate sale, and what remained was preserved at Emma’s shop. We must also adopt a little academic cynicism for an age when women still couldn’t own a bank account, and the gender pay gap was astronomical (VR being a major offender – some women were operating level crossing gates under their late husbands’ names for nothing!).

But even if Charles had found a shortcut to keep his trade going while dodging the rate collectors, the VR commissioners seemed convinced enough to title their final receipt ‘Emma Nettleton, Photographer’. And rich powerful white men hardly ever agree on anything not concerning those of their standing, so we can count this rarity for the books!

However, what really fuels my speculation on Emma being the true photographer is the quality and framing of the photos themselves. They are very different from Charles’ signature vantage-point landscape style, even though the assignment could’ve easily called for it. Where she can, despite the cumbersome setup, she gets close enough to include a human element alongside the railway miscellanea. She could’ve left them out, waited for a station to be empty or an engine to be unmanned; that was the real focus of the Exhibition after all. But this approach captures what I have known to be the truest purpose of the railways: the ability to move people, and weave stories through these movements – good, bad, and ugly ones all. More on that later.

My personal favourite is this shot of a level crossing gatekeeper with his family, both for the rare pictorial evidence of women in the railways and the delight so visible on all their faces at having their jobs recognised – just like the engineers with their locomotives, and the builders on the bridge.

Unfortunately, it would be Emma’s only recorded liaison with the lens. She put her shop up to let in 1887 – sadly it, along with Victoria Arcade, no longer stands today. Charles published his final collection of Melbourne photographs with an erstwhile business partner, John Mond Arnest, but in 1890 he saw the writing on the wall for wet-plate photography and drew the dark-room curtain shut for good. The couple retired to St Kilda to live with five of their nine surviving children, where Charles passed away on January 4, 1902. Emma followed suit almost exactly two years later on January 9, 1904, very close to the stately Albert Park Station – which she sadly didn’t get to photograph. I hope my efforts can do her justice.

Together with sweet young Elizabeth, they are buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery.

A quick but important detour: what was the 1886 Exhibition?

My reactions to most inventions of the British Raj range on a scale of cringing to loathing, and this is no different. The 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition was exactly what was said on the tin: a showcase of the British Empire’s extent and grandeur through palatial, exoticised displays (‘Courts’) of each of its ‘conquests’ abroad. With Queen Victoria having been proclaimed the ‘Empress of all India’ around nine years prior, India was the chief drawcard – hence its emphasis in the title – occupying a third of the exhibition, including massive, traditionally stylised gateways loaned from the Maharajas of each princely state.

The main purpose of headlining India as outlined by its Secretary of State at the time, the Earl of Kimberley, was to showcase its expertise in handicrafts; for he had ‘… often been struck with the calamity of the introduction of our taste into Eastern arts and manufactures, for their taste is far better than ours, although we have no doubt engineering and skill, and the command of capital…’

Yet despite these supposed good intentions, the final product and its depiction in British media took the usual ham-fisted Victorian approach of paternalistic voyeurism. The thirty-four ‘artisans’ that were on display at the Indian Court hard at work at a range of handicrafts from carpet-making to silversmithing to pottery were in fact inmates of the Agra Central Jail. They had undergone rigorous training in their given discipline specifically for the exhibition within the prison before being shipped off to this simulated recreation of an ‘Indian palace’ singing ‘barbaric chants’ as they worked – nameless, objectified products of the imperial gaze.

It was an arrangement specifically crafted to demonstrate to the public how ‘authentic’ Indian craftsmanship, with its painstaking labour and poor working conditions was inherently inferior to the fast-paced production of English factories, yet by virtue of being touched by ‘native’ hands and ‘historically pure tradition’ made them desirable for the Empire to covet.

Are you rolling your eyes yet?

If you want a more detailed account of popular (albeit insidious) reporting of the Indian Court and its image in the eyes of the British public, check out this excellent study by Aviva Briefel. For now, let us turn our attention to the Victorian Court, a much smaller but no less opulent showcase of the Queen’s shiny new gold-encrusted toy that was 1880s Victoria.

The exhibition catalogue’s introduction to Victoria reads like a copywriter gone wild. It lays heavy emphasis on Melbourne once being ‘broken forests’ and a ‘flooded quagmire’ before being flattened and paved with facades rivalling the wealthiest in London. The era’s typical reporting style makes bold claims such as ‘everything necessary to make life content and easy can be procured in Melbourne’ and ‘there is less drunkenness in Victoria and as little crime as anywhere in the world’. Sure.

A noticeable divide emerges here: how Melbourne (and all Victoria) was to be presented as a place where respectable British citizens could live without eschewing their British identity – made clear from the complete absence of Indigenous Australians in the writing – while India was a piece of ‘native authenticity’ that they could own while residing in these fashionable locales. It is in these embellished surroundings that Emma Nettleton’s photographs find themselves, a triumph of the VR’s ability to ‘tame’ the land into whisking prospective émigrés to all the ‘handsome’ towns you could see represented in the Court.

Does this make Emma complicit in furthering the colonial agenda? As with most historical accounts of everyday individuals, the answer is yes and no. It wouldn’t be surprising if she held the same beliefs and called herself a proud subject of the Empire as did most people who made the passage to Australia at the time. But with her husband’s business insolvent and the VR looking for the easiest and cheapest way to procure professional photographs, the 1886 Exhibition would’ve been nothing more than an opportunity for a bit of extra cash through a sexist loophole.

And yet, the carefully considered approach to them allows me to put aside for a moment the complex circumstances they were crafted in. Especially when I stand in the same spaces, unusually yet ideally placed, watching time march and freeze through a different lens.

More than just photographs of trains

The railways of the two lands couldn’t be more different, despite originating from the same source. The Victorian Railways has been relegated to history; it lost the Melbourne suburban network to privatisation and its name to V/Line, thanks to the cost-cutting spree of the 1980s and 90s. Many smaller towns that hadn’t yet been vacated after the gold money ran out lost their rail connections altogether, a side effect of a branch-line system entirely designed around goods transport rather than the possibility of moving people around. The only regular interstate services are to Sydney and Adelaide – the latter being light on ‘regular’.

The Indian Railways, meanwhile, has stayed firmly in government control ever since the consolidation of individual British lines in 1944, and has expanded its coverage and rolling stock ever since. While it comes with the low quality of life and punctuality typical of a government enterprise, its highly affordable costs and interconnected nature has cemented it firmly in the public imagination and popular culture. From Phulkari fabrics embroidered with trains by 19th century Punjabi women, to the bloody attacks on trains during the Partition, to iconic train scenes in Bollywood romances – the railways have taken on a life of their own in Indian history.

Between these two worlds is where I stand. I grew up on the Indian Railways, taking 20-hour sleeper carriage journeys every winter break, memorising timetables and drawing fantasy lines in marker pen. They have remained a constant all through my adult life and immigration: the suburban network of Chennai has been replaced with that of Melbourne, and trips to my small university town with frequent visits to Warrnambool – unwittingly gazing over the sunken beams of the Schomberg.

And everywhere I go, I am photographing the trains, stations, lines, and signs. It’s a hobby built out of familiarity but comprised of small moments in history: a disused signal box here, a heritage locomotive there.

With these little joys however comes the odd sour grape, like the comment at Newport Workshops. A stark reminder that the Victorian railway enthusiast scene was and remains overwhelmingly male and white.

It can be off-putting at times, even patronising. I think of that time a few model railway builders in Chiltern offered me their condolences on the terrible derailment in Odisha – as if my brownness put the weight of the whole country on my shoulders. In a way it does, but that’s exactly why I’m here: forcing my way into spaces that are not traditionally used to the idea of someone like me being there, bringing a different perspective to the dominant Eurocentric image of the railways. An ideal that moves people first and power second.

It sounds like trumpet blowing, but I see myself – and all my queer, BIPOC friends making inroads in colonised spaces – as one of many agents of change. A definite leap from Emma Nettleton signing an underpaying contract to exhibit her talents, buried within a showcase of inherent racial inferiority – and yet, 140 years later, there’s still a long way to go.

It’s why you keep at it, y’know?

References

Cato, J, ‘The story of the camera in Australia’, Georgian House, 1955

Lubbock, B, ‘The Colonial Clippers’, James Brown & Son, 1921

Official Catalogue, 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition

Briefel, A, ‘On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition’, Branch Collective

The Argus (Trove)

The Age (Trove)

My love as always to Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum, Warrnambool

Thanks to Hemei for putting up with my connect-the-dots and being my sounding board

Special thanks to Public Records Office Victoria (PROV) for helping me locate the records of Emma’s tender and working with me to digitise her images for all to enjoy!